Note: I am posting this blog early, because when it shows up on the blogsite, Susan and I will be away on vacation. We’ll be leaving our computers and all thoughts of publishing behind for ten days. Please do feel free to comment, and I’ll try to respond when we return. By the way, this blog is a rerun of one that I posted a could of months ago on the Oak Tree Press blogsite. I think it still holds up, and it’s even more current as the pub date for BEHIND THE REDWOOD DOOR approaches.

I moved to a small town in Humboldt County, California almost ten years ago, and I’ve wanted ever since to write about Humboldt’s amazing geography, its scenery, its history, its economy, and mainly its people. The trouble is, I write fiction—mystery fiction—in which people get killed and things sometimes get ugly. I didn’t want to paint my home town and my home county in a bad light, and I didn’t want to get in trouble with friends who don’t understand the difference between “normal” life, where conflict is to be avoided or quickly resolved, and fiction, where conflict is required and even relished.

So how could I celebrate this remarkable place, this land of rocky coastline, rugged mountains, and forests of towering redwood trees; this gentle balance between meadows full of peaceful dairy cows, fishing harbors, town squares, friendly taverns, and Victorian houses; a land rich with the history of lumbering, salmon fishing, and Native American culture? Not to mention the illegal cash crop for which Humboldt County is best known. Can’t leave that out.

Problem: I don’t want to tick off the authorities. Do I want the county sheriff, the city police, or the town council to get their feelings hurt by this newcomer, this mystery writer, who thinks law enforcement can sometimes be inept or corrupt? No way.

Problem: I don’t want to do a lot of research on the history of Humboldt County and try to get it right but inevitably get it wrong in the eyes of some local historians, because the history of this county is to a large extent a matter of contention.

So I’ve done what we all do in this business. Made it up from scratch. Forget research. Forget the facts. I kept the salmon fishing and the logging and the Native presence and the scenery. I kept the mountains, the redwood forests, and the rocky beaches, the town square and the friendly bar. But I have peopled the place with fictional characters who have somehow become realer to me than the people I meet on the streets, roads, and trails when I’m not writing.

Novelists get to do that, and it feels powerful and fun. We are historians of feuds, fights, and fanfares that never happened. We tell the truth about a bunch of lies. We dial up the drama of “reality,” in the interest of entertainment. And sometimes people get hurt. Some even get killed. Too bad. Some people fall in love. That’s nice, unless it’s also too bad. Love and death. It happens to us all.

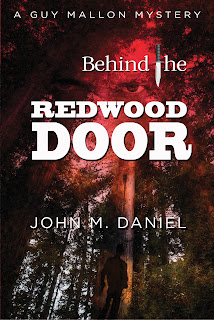

And in fictional Jefferson County, California, up in Redwood Country between the rocky Pacific shore and the Jefferson Alps, you’ll find love and death in high gear. I invite you to come and visit me in Jefferson County, by reading my new mystery novel, Behind the Redwood Door, in late November, when it will be published by Oak Tree Press. Be assured that I will contact you when that happens!

Meanwhile, here’s a teaser from the book. It’s from the only chapter that takes place outside Jefferson County, in the nearby county of Humboldt.

“Tell me something, Guy.” We sat beside the Mattole River in southern Humboldt County. High hills rose all around us, some of them covered with forests, others open fields of golden grass. The river was low and lazy this late in the summer, and dragonflies danced across the surface. A hawk wandered in the sky high over our heads, crying, crying. The riverbank was a small field of cobblestones, and that’s where we sat eating the sandwiches we’d bought in the one-store town of Honeydew, just a few miles back. Turkey sandwiches, Fritos, and cold local beer on a hot, still afternoon, with no pressing agenda except to get back to Shelter Cove in time for dinner. I hadn’t felt this relaxed in weeks. “Tell me something,” Carol repeated.

“Hmmm?”

“Why is life with you such a dangerous road?”